Interview with Michael Murphy

Michael Murphy on Bringing Ritual Back to Mourning

Among the products in The Solace shop is a limited series of hand-carved keepsake urns by Wicklow-based craftsman Michael Murphy. We spoke to Murphy about his approach to working with wood, his thoughts on death, and how these pocket-sized vessels offer a tangible way to stay connected to someone you’ve lost.

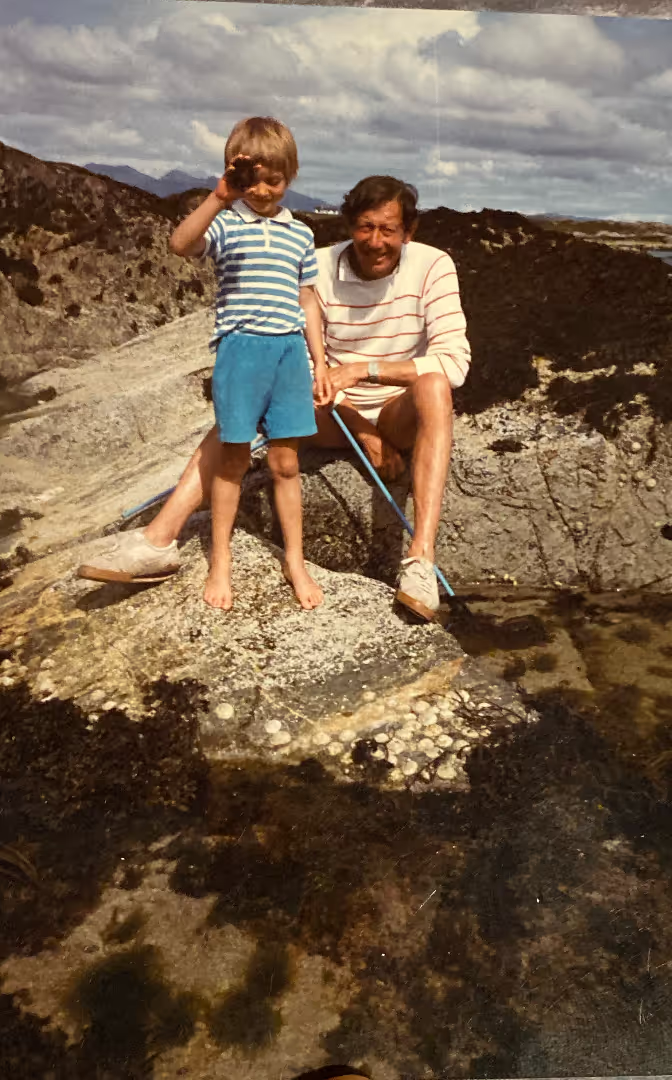

You might think a small memorial urn would be one of woodworker Michael Murphy’s more unusual commissions, but he assures us it’s not. “I’ve been asked to remake a broken gunstock for someone’s Grandad who used it to save himself when he had no bullets at the Somme. I’ve made honey dippers for pagan rituals, all sorts of strange things,” he reflects. Perhaps it’s the raw and ritualistic nature of Murphy’s work that attracts this type of project. Working out of a converted potato shed tucked away on a narrow lane in Delgany, co. Wicklow, Ireland, Michael works with local Irish wood using traditional hand tools and techniques. The vessels, furniture, cutlery—and more recently, urns— that he creates are rooted in Irish culture and often decorated with tactile surface textures, which he gouges by hand using a relief carving technique that is hypnotic to watch.

“I develop a deep relationship with these artefacts, I care for them and the trees they come from.”

“When I find my rhythm, the thousands of tiny gouge marks that decorate the surface of these pieces become automatic,” he says of the meditative process. “My hands take over and the mind drifts. I develop a deep relationship with these artefacts, I care for them and the trees they come from.” The urns that Michael has crafted for the Solace fit snugly into the palm of your hand or into a pocket and are made from a light-coloured lime and dark walnut—both woods from native trees that are easy to carve.

Made of two halves, each urn features a painstakingly carved dovetail mechanism that seamlessly slides open to reveal a concealed glass compartment inside for keeping a small amount of your loved one’s ashes. This clever and incredibly precise opening and closing movement provides a sense of intrigue and ceremony—a hallmark of Michael’s work. Meanwhile, the playful shape—based on the smooth sea-worn pebbles you find on the beach—is designed to be soothing to hold, each one similar but slightly different. Tactile but not too busy. “It’s something you can hold in your hand, and keep close,” says Michael, “a gentle reminder of someone's life.”

“It’s something you can hold in your hand, and keep close,” says Murphy, “a gentle reminder of someone's life.”

Michael works exclusively with local timbers, using either storm-felled trees that he processes and dries out over a year, or he’ll source wood from his local sawmill. The wood used in his first batch of vessels is sourced from lime and walnut trees on the nearby Kilruddery Estate in Co. Wicklow—species which, he says, “take detail very well”. Michael takes the rough boards and flattens them down, cuts them to width, and then cuts the dovetail. “I have to make the male part and the female part, and they have to be incredibly accurate. If it's too loose, it'll just slide apart and if it's too tight, they won't be able to open or close it. It's a half-a-hair sort of tolerance.” After this, he starts shaping the keepsake urn using a knife and an axe—a fiddly process on such a small object. Once the shape is refined, he gouges the surface to create beautiful textural markings, coats them with beeswax, and then burnishes the surface with rocks to create a harder texture.

Michael, who honed his craft over the course of ten years before setting up his own practice, is driven by his passion for making. After studying for a law degree, he took the unusual decision to transition into furniture making, learning the ropes with an Irish maker in Australia before moving back home to Ireland where he worked in another studio, where he learned how to do everything from metalwork to thermal welding. He began his solo practice almost by accident during Covid when an Instagram page he created about spoon-making unexpectedly took off. Today, he works from his Delgany workshop, slowly working his way through a pile of timber offcuts, creating whatever takes his fancy and selling the results to private clients and galleries. “It's led me on a strange road of making weirder and weirder things,” he smiles, “culminating in making urns for the dead.”

“Creating modern artefacts that can bring a sense of ritual back, especially into something as significant as death, is something I am very attracted to, actually.”

The idea of creating modern artefacts is a concept that Michael references a lot in his work, describing his style as “future vernacular”. Through the objects he creates, he tries to imagine what Ireland’s material culture would be like had the country not been invaded for 600 years and become part of an empire. “Things have become so homogenised in terms of our material culture, and so much ritual has been removed from daily life, that I think creating modern artefacts that can bring a sense of ritual back, especially into something as significant as death, is something I am very attracted to, actually.”